Learning Boosting Through Me Getting Fired from Tutoring

My Employment History

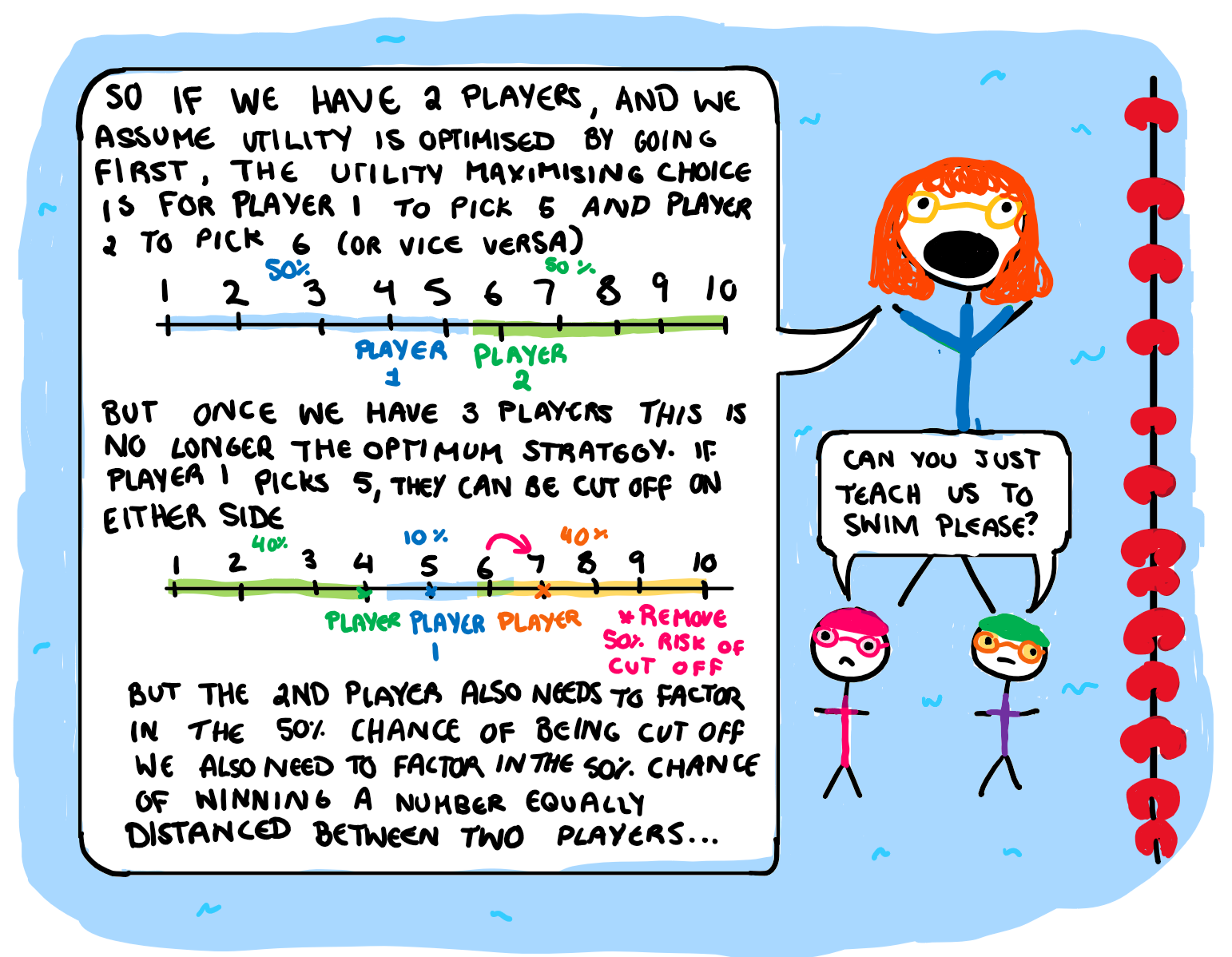

I’ve had about… 13 jobs at this point in my life. Among them were jobs like tutoring, nannying, swim teaching, ect. so I have developed had a decent level of experience in teaching kids, specifically teaching them maths. While swim teaching doesn’t seem like it employs a lot of maths, I would play a “who can get closest to the number I’m thinking” game to decide who goes first. I then used it to explain game theory and how to optimise their strategy based on what the other kids would pick if they were acting as rational agents. They didn’t fully understand, but it was a fun exercise.

I was never a very good tutor because I have a tendency to overcomplicate simple problems, and argue with the student’s teacher or parent. A recurring personality trait that is likely apparent after reading enough posts from this blog. The worst case of this was when I was fired from my tutoring job several years back. But what do my failures as a tutor have to do with boosting?.

Why Boosting Reminds Me of Tutoring

I have always seen boosting as the one of the most intuitive ensemble methods. For anyone who doesn’t know, an ensemble model combines many individual models to create one aggregate model that tends to have greater accuracy and less variance than any of the individual models. Think of it as the machine learning version of everyone voting to make a decision instead of a single expert making a decision. If we relate them to human studying, boosting is like doing every question at least once and then only revising the questions we previously got wrong. This makes boosting more similar to the way I study, and try to teach my (previous) tutoring students. In machine learning, boosting builds the models sequentially where each new model is built on the residuals of our current model, and only takes a small amount of predictive power from each (known as the learning rate). To see how this in action, lets look at the animation below.

Here, I have made a boosting model using 50 regression trees that each consist of a single split, and have a learning rate (how much information we take from each tree) of 0.1. The colour represents the value for y. In the background we have the current predicted values for that area, and the actual data we are working with in the foreground. The size of the data represent the current error for that observation. It is pretty apparent that the data points become smaller as the background (predicted value) more closely resembles our training data. Each dashed line indicates the most recent regression tree (or in this case stump) that has been added to the model. Since this is a model that progressively learns, both the error and prediction change as we incorporate more and more models. Now that we have a visual on how boosting works, lets talk about tutoring.

Part 1: Focusing on Mistakes

If you get 100%, You don’t need tutoring.

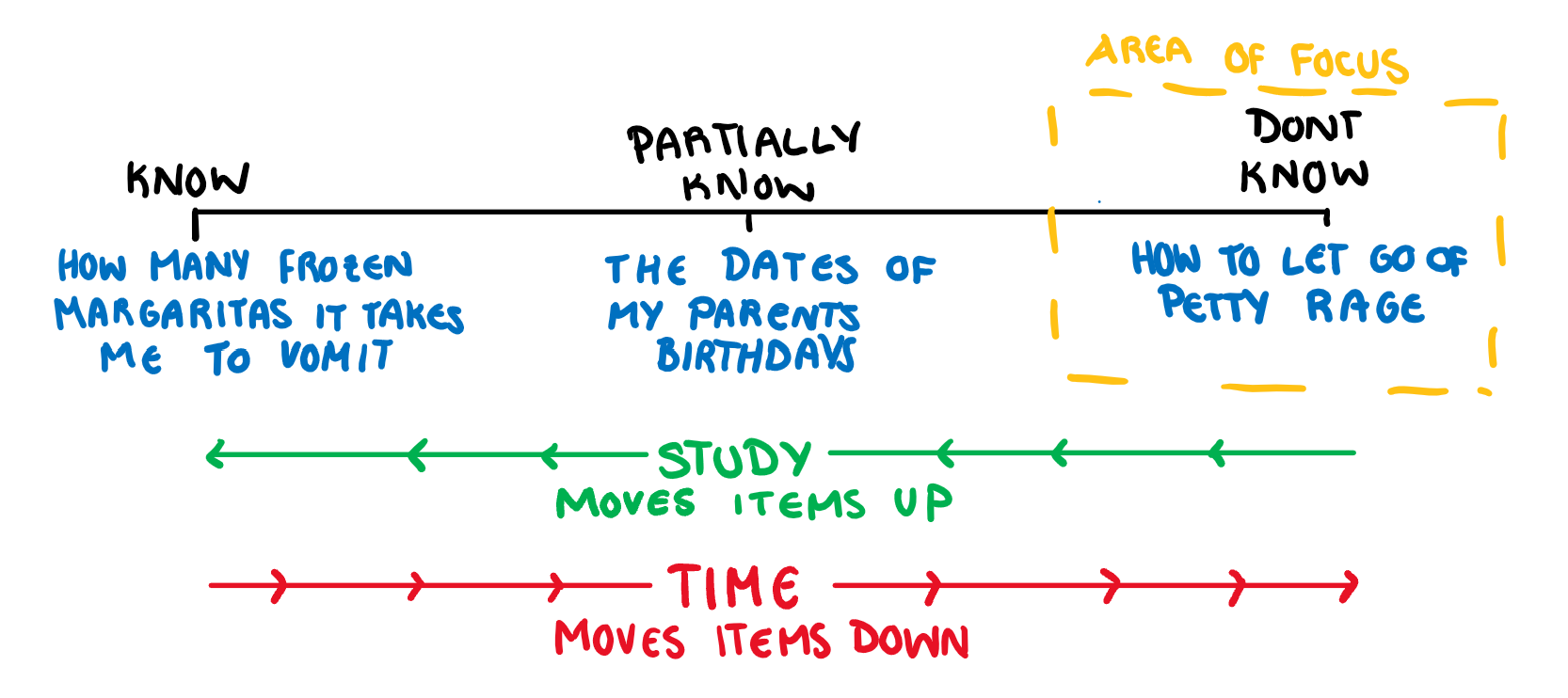

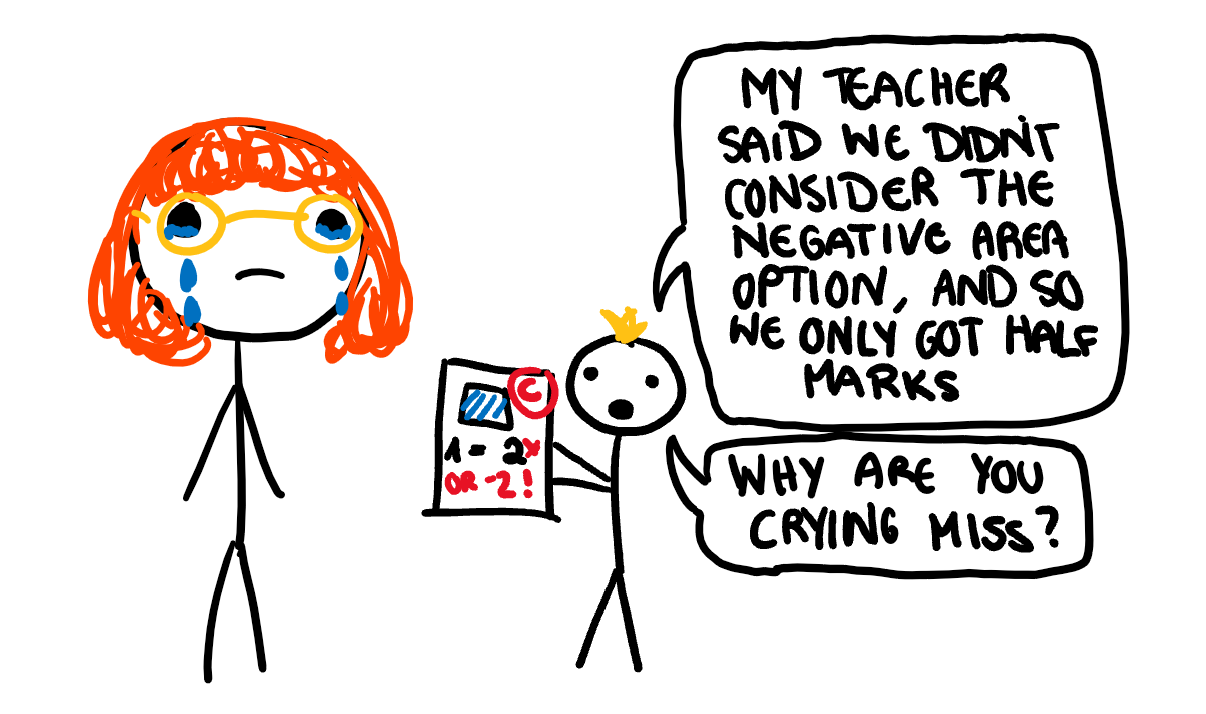

The interaction that got me fired from my tutoring company was with a kid I’ll call, Riley. After being begged to take him on as a student (he was a 5th grader and I teach high school maths) they sent me the information I needed to teach Riley. The first was an email from his teacher that read like this: Hi Mrs Riley, I’m not sure why you are getting your son tutoring considering he has no trouble in class. I have nothing he needs to work on. Maybe the tutor could teach him next semester’s content, but then he would just be bored in class so I wouldn’t recommend it.” I think, great, not only does this kid not need tutoring, but his parents are actively going against his teachers advice. Not a good sign. Next I read a note from the last tutor. “I just bring a computer game or a worksheet for him to do, and then mark it” Double great. This comment was even worse. I was clear this kid had nothing to learn, so it didn’t matter what the last tutor did with him. A tutoring session of watching a kid do things they already knows how to do with no useful feedback can go completely unnoticed. You get the most “bang for your buck” focusing on your worst areas, as they are both the areas requiring the most improvement, and are forgotten the fastest. I incorporate this attitude to every aspect of my life. You can see how in the visual below.

If you are just revising things you already know with 100% accuracy, you are not learning.

Building Models in the Residual Space

If we build an ensemble model that is 50 models, each identical and with perfect predictions, we get the same result as if we made one. This is just wasting computational power much in the same way Riley’s family was wasting money on tutoring. In boosting, since each model is built on the residuals of previous models, it is trying to make sure that it does not repeatedly learn things it already knows. The model focuses on the most common, frequent, and damning errors, and works its way back from that. In the first animation, I let the size represent the errors, but each model is not built using the response variable, it is built using the residuals. Here, using the exact same data and model above, I have instead animated each individual tree as it tries to predict the residuals.

We can see that when we start our boosted model, the residuals are essentially our y value (since the initial prediction for the whole area is 0), and as the main model becomes more accurate, the residuals become 0, and new trees don’t have any information to contribute to the model. If the model continued much further, it would just randomly build trees on the irreducible error.

By focusing on the residual space, the model ensures that we aren’t wasting computations by relearning something we already know. In a similar way, the best way to learn as a human is not to revise the areas we get 100% in, but rather the areas we are failing in as they offer the most room for improvement.

Part 2: The Learning Rate, The Number of Models, and The Model Complexity

Rash Decisions in Tutoring Is a Dangerously Simple Method

When I arrive at Riley’s house, I explain I don’t have any computer games or worksheets because I disagree with them morally, however I could cover future school work and invent some fun questions. Riley’s mum was not a big fan of my moral plight to take down “big tutoring”. After a brief discussion about how “we are all a little disorganised” which everyone knows is mum code for “you are disorganised”, she sent me home. Later I received a call from my boss about being “ill-prepared” because I should have just brought computer games and worksheets like the last tutor recommended. I explained my side, and by boss was sympathetic, but I never got another tutoring job from them again. Unfortunately, due to Riley’s mum being unsupportive of trying new teaching methods, the best speed at which Riley should cover new content wont be found. He might have learnt better with longer sessions, or with another student, or doing literally anything other than playing computer games. Much in the same way that we can tailor the environment and complexity of a tutoring session, boosting can improve its predictions by changing the learning rate, number of models and the model complexity.

Tinkering the Complexity of the Boosting Model

When using boosting, we need to be aware of how the learning rate (or shrinkage), the number of models and the model complexity impact our final prediction. The learning rate decides how much “predictive power” we take from each trees. Smaller learning rates need more models to get a working prediction, larger learning rates run the risk of giving too much power to outlier models, and missing minor complexities. The number of models (trees in our example) is just decided in parallel with the learning rate, and is essentially how much computational time we are willing to dedicate to our model. The depth of the tree is similar, in the sense that with enough trees, a stump tree can capture any relationship, however if we don’t have the capacity for enough models, we can increase the complexity of each individual model to add more nuance to the final prediction.

Part 3: Need to Know When to Quit

Overfitting in Learning

I know someone has spent too long studying when I see forum posts asking if some obscure topic is going to be on the exam. Once you have run out of things to focus on that are important, you start to focus on the things that are less and less important, until you are sitting awake at night crying about the sheer vastness of knowledge that you could never hope to learn. Knowing when to quit is an important part of life and machine learning. Most people tell other to “try try and try again” my motto is “if you aren’t feeling it, quit”. After several years of tutoring, I was no longer feeling it, and it was time to quit. It turns out repeatedly being told “the continuity of functions doesn’t matter” and “dividing a number by 0 is 0” my soul had been crushed and I wasn’t doing my job properly any more. I had too much baggage and it was time to quit. Just like with tutoring, boosting needs to know when to quit too.

Boosting can Overfit

Unlike in bootstrapping, boosting has the potential to overfit. Since the later predictions are the cumulative prediction of all the models that came before, and the new models are only concerned with what those models got wrong, the overall benefit of each model is less than the model before it. This means that eventually, the tangible benefit of building a new tree becomes zero. Because of this, we always need to be aware of our ensemble complexity and manually set a stopping criteria.

Conclusion

Boosting employs three techniques that make it similar to effective human learning. First it focuses on mistakes, secondly it is important to tailor the complexity of any one session, and finally it need to be manually stopped or otherwise your model will stare into the abyss of the unknowable in existential dread.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.